Facts and Figures

1.

Bidjerano, T. (2010). Self-Conscious Emotions in Response to Perceived Failure: A Structural Equation Model. The Journal of Experimental Education, 78(3), 318–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220970903548079

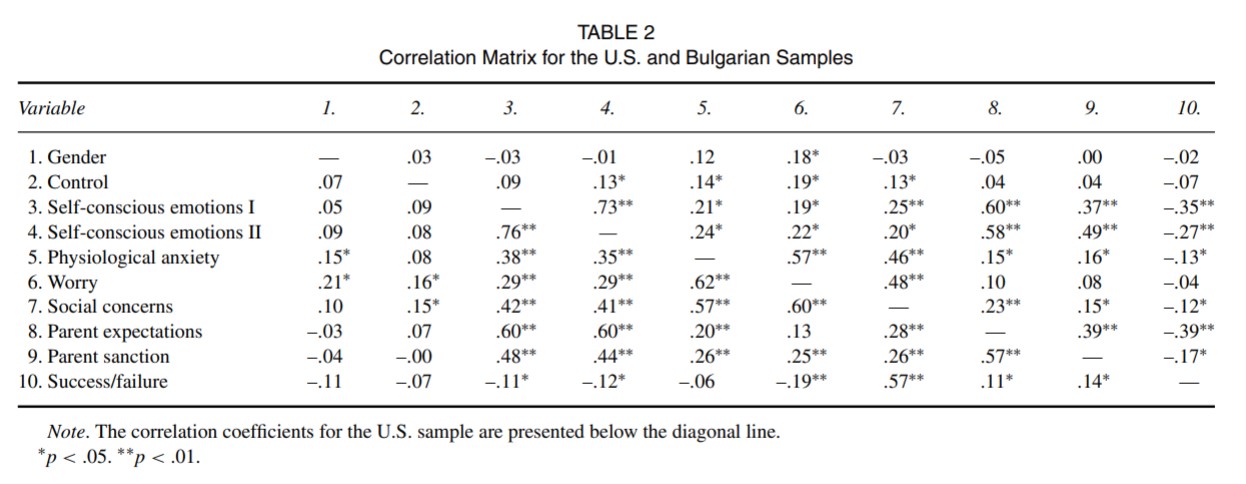

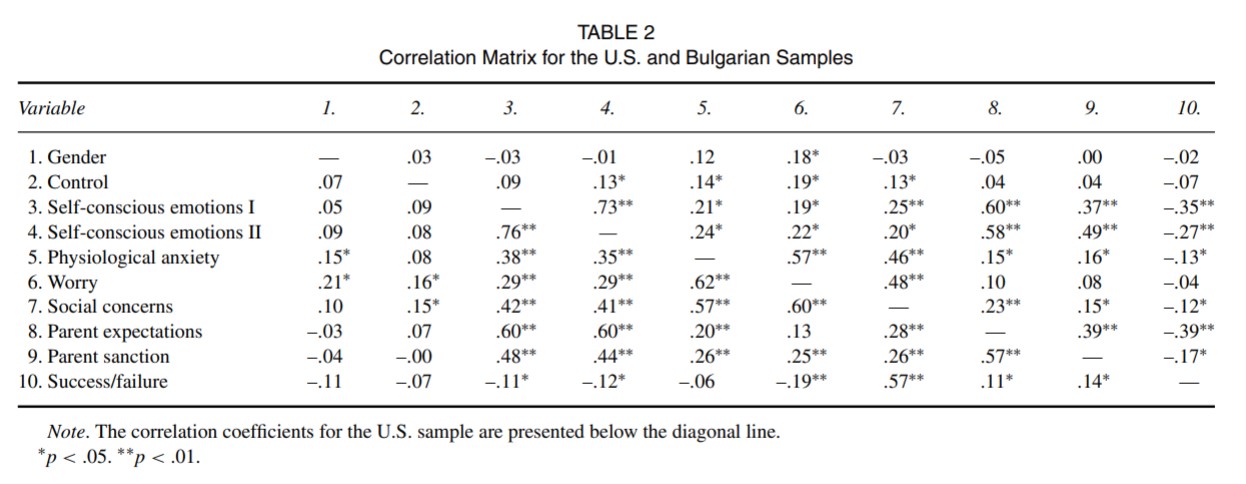

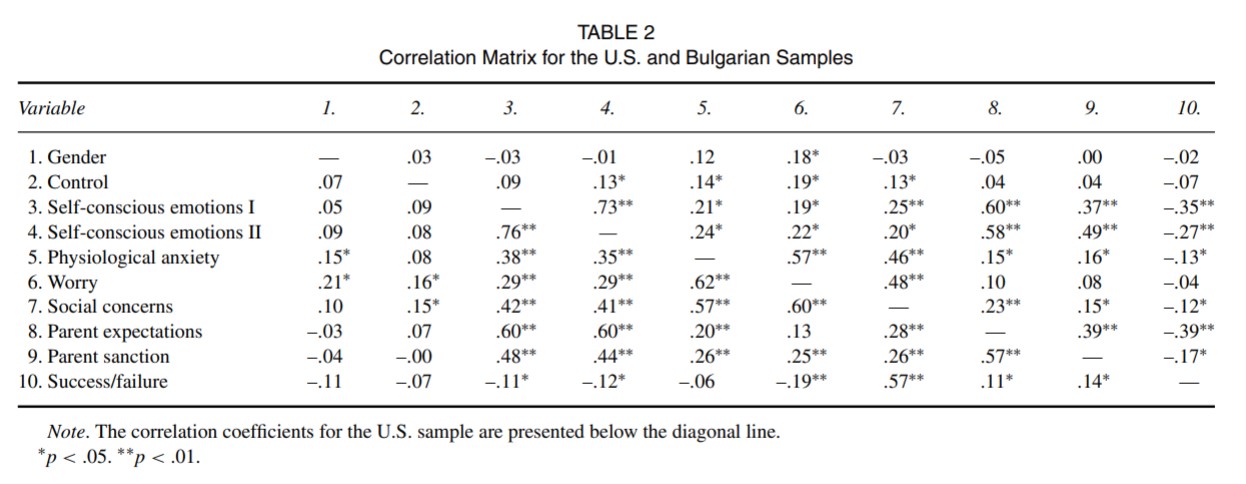

Bidjerano (2010) sought to explore the prevalence of self-conscious emotions, such as shame, in response to a perceived academic failure. The study focused on 4th grade students in the United States and Bulgaria, representative of individualist and collectivist ethnotheories. Bidjerano administered a series of questionnaires centered on measuring emotional arousal, the consequences of parental expectations, and parental action in response to the perceived failure. Table 2 shows a significant correlation between success/failure and self-conscious emotions; parent expectations and success/failure; and parent disapproval/sanction and success/failure. The association of these variables shows the direct effects of parental control and gender on anxiety. However, culture is cited as playing a role in the frequency by which emotions are used in the socialization process. According to Bidjerano, self-conscious emotions are utilized more frequently when the behavior is considered to violate social norms (p. 322).

2.

Helwig, C., To, S., Wang, Q., Liu, C., & Yang, S. (2014). Judgments and Reasoning About Parental Discipline Involving Induction and Psychological Control in China and Canada. Child Development, 85(3), 1150–1167. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12183

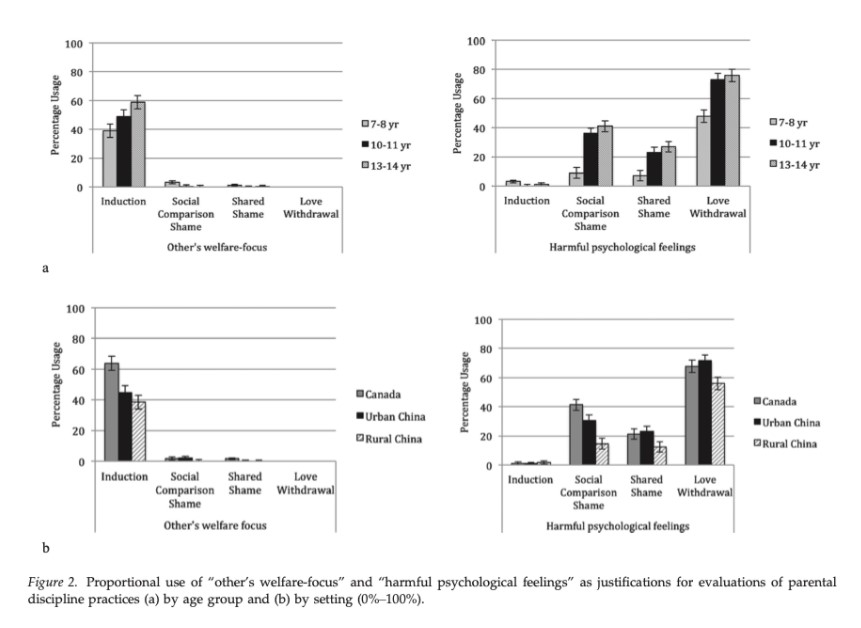

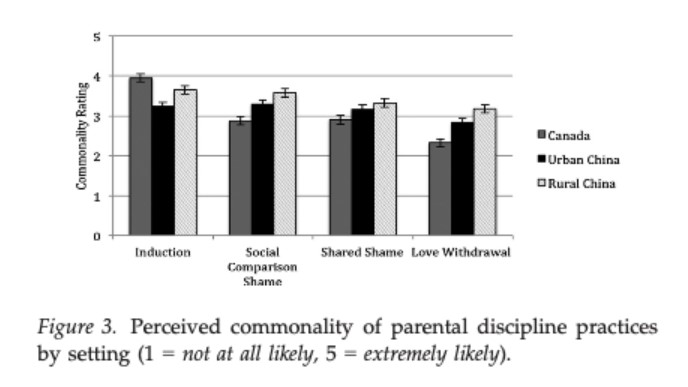

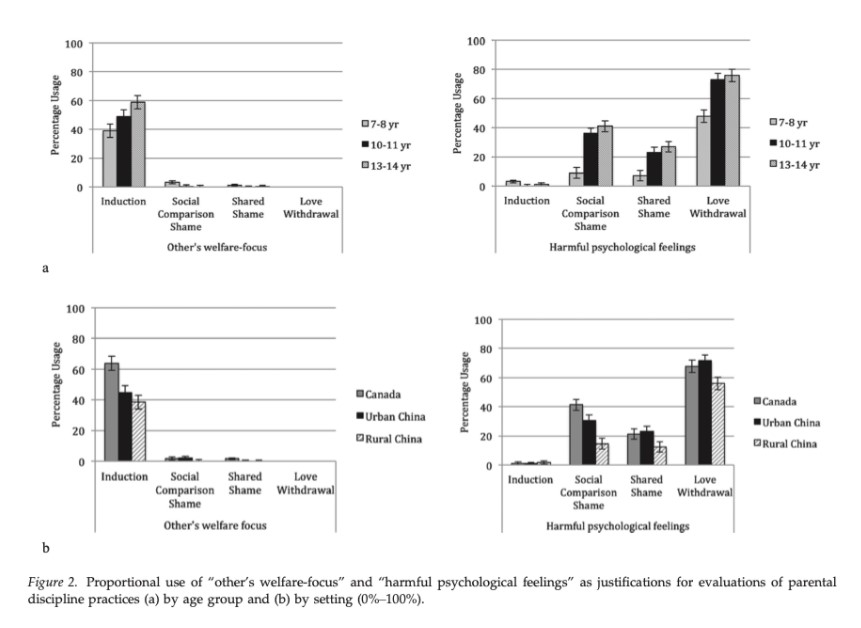

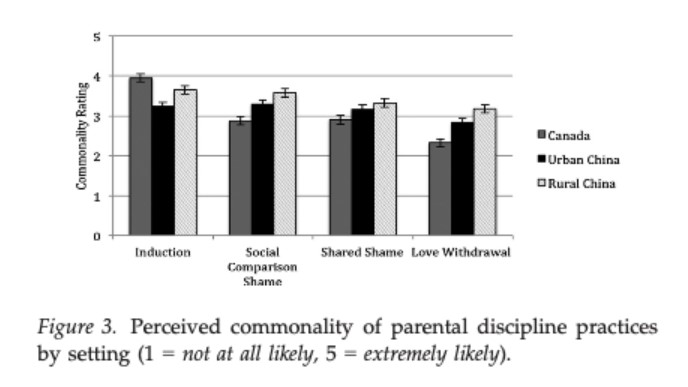

Helwig et al. (2014) examined child reactions to four different parental control methods including two forms of shame, social comparison shame and shame sharing. Children in three locations (rural China, urban China, and Canada) were administered vignettes that depicted a scenario by which a child breaks a social norm. The children were asked to evaluate the four parental responses on their effectiveness, whether or not they believed the response was harmful, and estimate the frequency of the technique in their communities. Figure 2 shows common responses among different age groups and then by culture. We can see that all age groups rated induction as being the least harmful to the child while love withdrawal and social comparison shame were considered the most harmful. However, the rural Chinese group rated all forms of shame and love withdrawal less negatively than the Canadian and urban Chinese. This could be related to the findings in Figure 3, wherein the rural Chinese group rated both forms of shame and love withdrawal as common in their community. Referring back to Bidjerano (2010) this could change the children’s perception on the use of self-conscious emotions in the socialization process. However, the distance between the three setting groups also shows that previously understood differences between individualistic and collectivist cultures and their understanding of shame in child rearing may not be as drastic as previously hypothesized.

3.

Sznycer, D., Tooby, J., Cosmides, L., Porat, R., Shalvi, S., & Halperin, E. (2016). Shame closely tracks the threat of devaluation by others, even across cultures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(10), 2625-2630. Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26468599

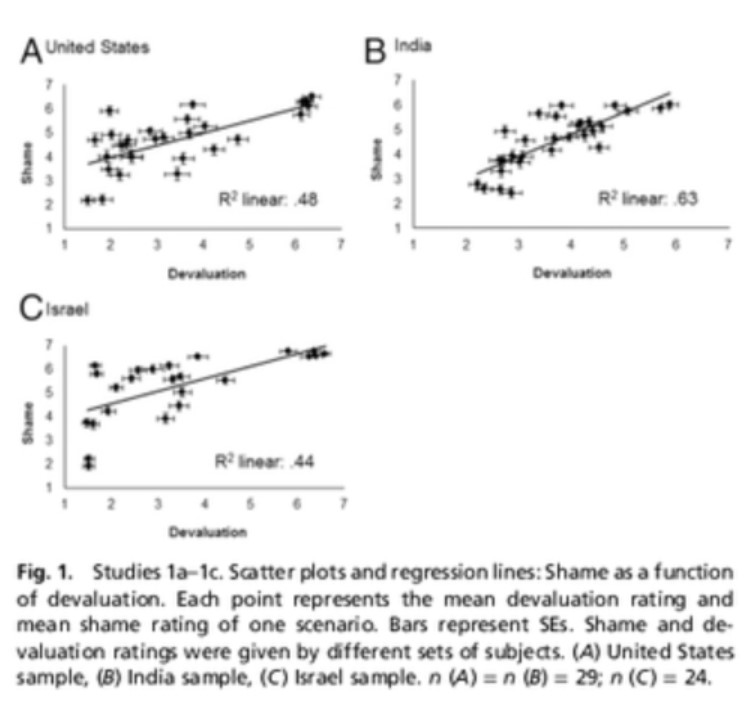

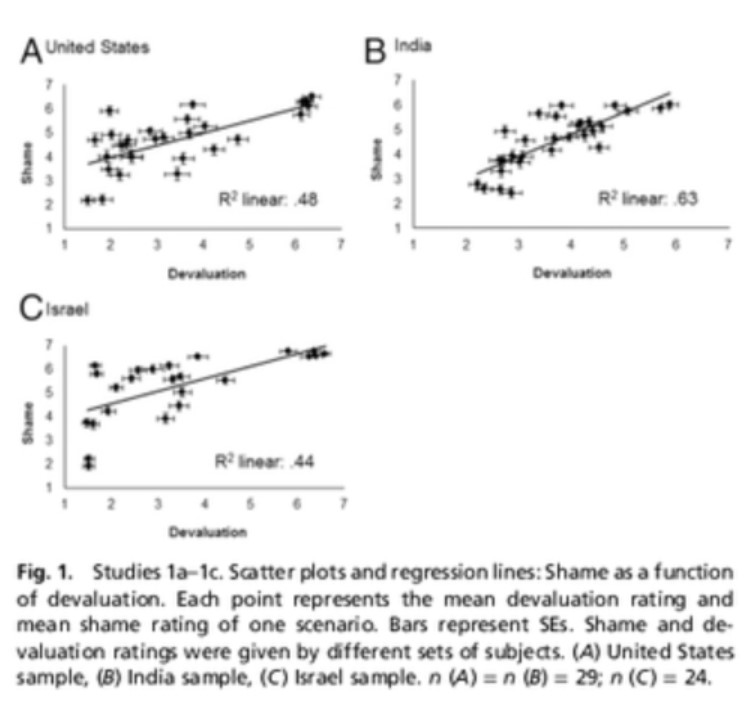

Sznycer et al. (2016) explored shame as an evolutionary function that developed to prevent the individual becoming devalued by his or her community. Participants were given 29 scenarios in which the protagonist’s characteristics or actions are considered negative. The participants were then asked to indicate how they would feel if they were the protagonist and to indicate how they believed a community would react. Figure 1 shows shame as a function of devaluation, or the degree to which the shamed individual is devalued by their community and the perceived devaluation as rated by the respondents. These results show that shame is highly correlated by perceived community devaluation, even across different cultural contexts.

Title Page